Nuclear missiles were once ready to launch from Milwaukee's suburbs

Escalating tensions between President Trump and the dictator of North Korea over that country's nuclear capabilities have recently stoked fear, but there was a time the threat of nuclear annihilation was so great warheads were ready to launch essentially from the backyards of Waukesha homes, and other locations ringing the Milwaukee area.

“For someone today who didn’t grow up during the Cold War that has no idea what the Berlin Wall was, that doesn't understand what the ramifications were if we lost the Cold War: We would have had Russian sickles on our flag,” said Chris Sturdevant, the Cold War Museum’s Midwest chapter chairman. “It's that simple.”

Sturdevant wants to build a Midwest Cold War museum and he thinks the ideal location is at Hillcrest Park, 2119 Davidson Road, where the remnants stand of a radar site that was once considered by the federal government to be the first line of defense against a nuclear attack.

Today, not much remains of the missile installation. But there's an ongoing effort to remember the history of the site and the realities of the Cold War era.

The First Line of Defense

The 13-day standoff, known as the Cuban Missile Crisis, began on Oct. 16, 1962 when President John F. Kennedy was briefed about a Soviet-backed nuclear arms build-up in Cuba.

“We came as close that week to nuclear war than we have ever had before or since and, if you can imagine what it was like, we were the last line of defense established to protect the metropolitan areas of Milwaukee, Chicago and Gary, Indiana,” said Colin Sandell, a veteran who worked at the radar base in Waukesha.

Sandell’s first day on the job was Oct. 19 of that year – squarely in the middle the Crisis. He started as a range operator at the facility, which was used to detect squadrons of Soviet bombers, and later worked with the missile tracking radar.

When he was sent to the radar installation, now Hillcrest Park, the base was on high alert.

Concerns of nuclear war shot across the country, and the base was “locked and loaded,” Sandell said.

“If the Russian long range bombers were coming over the poles we'd be the first guys to have a chance to knock them down and we were … ready to fire.”

“It was a really tense time for that first week in October of 1962,” he said.

Missile defense system

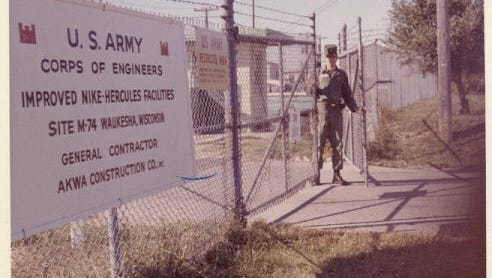

In 1956, the AJAX Nike Missiles were brought to the Milwaukee area where eight missile bases – in Waukesha, River Hills, Cudahy, Franklin, Muskego, Lannon, one on Silver Spring Drive and Sherman Boulevard and one on the current Summerfest grounds – were established to defend the area's population and industry.

The missile defense system was divided essentially into three parts: defense rockets, which would be launched against attacking intercontinental ballistic missiles; radar equipment that would find incoming warheads and plot their trajectory; and the computers that would make the rapid calculations to intercept the warheads.

The eight bases were reduced to three in 1959 – Waukesha, River Hills along Brown Deer Road, and the Summerfest grounds – and the Ajax Nike missiles were replaced with Nike Hercules Missiles capable of carrying nuclear payloads.

Sturdevant, the midwest chapter chairman of the Cold War Museum, said the army realized conventional warheads wouldn’t be effective against a formation of Soviet bombers.

“They needed a heavier payload, so to speak, to take on such a big squadron of fighters or bombers should they have gotten through. That was the reasoning or rationale of deploying nuclear missiles because they could indeed take out several (bombers) at a time,” he said.

Consequences of nuclear defense

If Soviet bombers flew over the Arctic en route to bomb the U.S., the fight would have likely taken place in Canada “where there is a very low population,” Sturdevant continued.

“(The North American Aerospace Defense Command) called it the distant early warning line. Then they also had the Canada line. If the (Soviets) got beyond those two points that meant they were over our airspace here in southeast Wisconsin,” he said.

If the bombers ever did manage to fly into or near U.S. territory, it could have been disastrous for communities caught in the middle of the conflict.

The nuclear payload attached to a Hercules missile would be similar to the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during WWII.

“The missiles themselves were aimed at areas like Oshkosh (and) Appleton so again the fight would have been further north of southeast Wisconsin,” Sturdevant said. "But nonetheless, if you're talking about a 15 kiloton weapon (to) 30 kiloton nuclear bomb then (the U.S. would have to deal with) the radiation and the fallout that would have occurred over our own territory.”

Sandell, the former Waukesha base operator, said he believes a launch of the defensive missiles would have exploded somewhere over Sheboygan, Manitowoc, Fond du Lac or Oshkosh 20,000 feet to 30,000 feet above ground.

“A nuclear explosion would pretty much destroy everything underneath it,” Sandell said.

He said the aftermath of using the defense system was something nobody ever talked about, not even in the communities where the bases were stationed.

“There is no way I could see the communities tolerating having those kinds of weapons in their backyards anymore …. It shows you how concerned people were about being attacked by the Soviet Union.

“Even if they thought about it they didn't say anything,” he said, “they didn't object."

Relevance of the Cold War

So why does all this matter now?

Perhaps because history in the U.S. is too easily forgotten and too infrequently instructive, said Francis Gary Powers Jr., the founder of the Cold War Museum in Warrenton, Virginia.

"I would be giving lectures in high schools in the mid 90s before the founding of the museum,” Powers recalled. “I'd walk into a classroom to give a talk on the U-2 incident. (I'd) get blank stares from the kids, they thought I was there to talk about the U-2 rock band.”

His father, Francis Gary Powers, was a U-2 pilot who was shot down over the former Soviet Union on May 1, 1960.

“So that was the catalyst for the creation of the museum,” Powers said. “(It) was to honor our veterans, preserve the history and educate the students who didn't really know anything about the Cold War and it was only four or five years from being over.”

Powers stressed that it is important for people today to learn about the Cold War because the aftermath of that era is still impacting the world.

One example he cited was the so-called war on terror that the U.S. has been fighting for more than 15 years.

In 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, and the CIA supported indigenous rebel fighters against the invasion. The kicker: One of those rebels was Osama bin Laden.

“History is not just a period of time between point A and point B or time period A and time period B,” Powers said. “It is the evolution of events over time.”

The threat of nuclear annihilation was something people learned to live with during that era, but Sandell believes those attitudes are no longer holding.

"In the old days in the Cold War it was mutually assured destruction. That’s what kept each other from pushing a nuclear launch button,” Sandell said. “When you are dealing with people like Iran and North Korea they don't seem to be concerned about being obliterated. The Soviet Union (Russia) does. They have a lot to lose, so does China, but these other countries don’t.”

For Sturdevant, the Cold War and the local Nike missile sites are worth remembering because the era was the “longest and costliest conflict in our history."

Not only was the Cold War expensive, but it also led to inventions and innovations that have changed the U.S. and the world forever.

“The biggest reminder of the Cold War that we have … (is) the U.S. interstate highway system. . .. The internet is a function of the Cold War. It was initially tracking nuclear weapons out in the bay area in the 1960s,” Sturdevant said.

“(The history) is right in front of our noses.”

Preservation

Throughout the last decade, Sturdevant and the museum have presented the city of Waukesha with two proposals for building a Cold War museum at the former radar site.

What’s primarily halted its creation, he said, is cost.

“The big problem continues to be how do we reach that $300,000 price tag, and I think eventually it can happen, but it's going to take a little bit more planning on our part," Sturdevant said.

He contends the radar site in Waukesha is an ideal spot for the museum because hundreds of veterans spent time at the base at one time or another and because of the role it played in “fighting to protect (the U.S.) and prevent World War III.”

“The fact that we had nuclear weapons here in southeast Wisconsin is amazing,” Sturdevant said. “It makes sense to have it on a heritage site that would be becoming of preserving veterans efforts and the community during the Cold War."

Sturdevant says the next step in opening a Cold War museum in Waukesha is to create a committee to look into future and current options of displaying artifacts at the radar installation.

Regardless, he said, the Cold War Museum will continue to host educational programs throughout the Midwest.