New book looks at Mount St. Helens' deadly volcanic eruption

History’s ashes have fallen so heavily and with such variety since 1980 that, for many Americans, the eruption of Mount St. Helens — a long-slumbering volcano among the peaks of the Cascade Mountains — seems about as close to us as the lava that buried Pompeii.

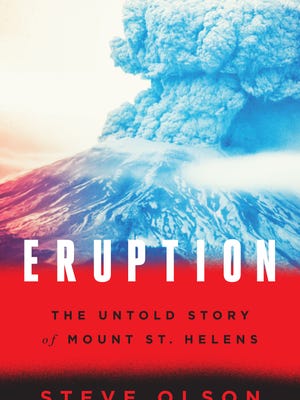

But, as Steve Olson reminds us in his vividly reported new history, Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens (Norton, 245 pp., **** out of four stars), what happened on May 18, 1980, in the primordial thickets of the Pacific Northwest, was an enormous, multi-faceted event.

The volcano had been dormant for 123 years, during which time the Indian trails of the region gave way to railroads, lumbering, and all manner of development. Indeed, Mount St. Helens lay mostly under the radar — and off the seismographs — amid this bustle of modernity.

When it blew in 1980, its force was more powerful than the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, Hurricane Katrina, even the first atomic blast of 1945. Devastating an area four times the size of Washington, D.C., it triggered a world-class landslide and, most tragically, killed people as far away as 13 miles from its summit (57 victims died that Sunday morning).

One could go on about its effects — ash deposited in 11 states, billions of dollars in damages — and Seattle-based Olson does. As one would expect of any first-rate reporter in today’s climate, he charts the impact of the blast on an exploited natural environment and refreshes our memory of the dead, and their humanity.

The result is a cast of well-drawn characters, from the scientists who were there — such as Dave Johnston, a volcanic gas expert for the U.S. Geological Society, and Donal Mullineaux, who had predicted the eruption in a report — to a slope-dwelling octogenarian named Harry Truman, logger John Killian, and Susan Saul, who led the Mount St. Helens Protective Association. Those who perished that Sunday are recollected by Olson in a cross-weave of purpose and passion that illuminates their fateful choices up to and beyond the volcano’s moment of indifferent fury.

At the cultural epicenter of the story lies George Weyerhaeuser, scion of the lumber dynasty that dominated the region, and CEO of the Weyerhaeuser Company in 1980. His firm was not only Washington state’s largest, but had a higher market valuation than Ford or Mobil at the time.

Weyerhaeuser owned almost all the land outside of the national forest area of the volcano’s western and northwestern sides, and industry pressure had an impact on the drawing of the “red and blue zones” that demarcated safety around the volcano once it became active again on March 20, 1980 after a 4.2 earthquake — and which were proven wrong by the eventual eruption.

“The geologists and law enforcement personnel were not happy with the danger zones,” writes Olson. But the forces of man and nature, so often at odds, were on a familiar collision course, and this engaging book maneuvers deftly along the way toward impact.