Calif. end-of-life law, inspired by Brittany Maynard, to go into effect

(RNS) — Somewhere in California on Thursday, a terminally ill person may lift a glass and drink a lethal slurry of pulverized prescription pills dissolved in water.

And then die.

That’s the day the nation’s most populous state implements a law, passed in 2015, making physician-assisted dying accessible to 1 in 6 terminally ill Americans, according to its national backers, Compassion & Choices.

Similar laws are already in effect in Oregon, Washington and Vermont. In Montana, the state Supreme Court ruled in 2009 that assisted dying was legal under the state’s Rights of the Terminally Ill Act.

“Normalizing” this process is the term big with supporters. It conjures a sense that this is the last autonomous act of a person who, two doctors must certify, is six months from death’s door. Although the option is a multistep process that can take a few weeks, it can short-circuit months of intractable pain and suffering.

The real killer, in this view, is the terminal illness or injury. A lethal prescription, which the law dictates only the patient can administer, merely changes the timing.

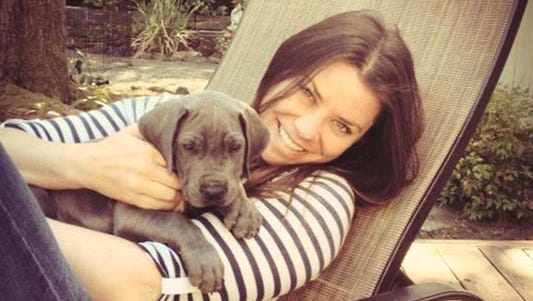

That was the view of 29-year-old Brittany Maynard, one of the people who inspired the California law.

In 2014, she was a California newlywed who refused to allow an incurable brain tumor to overtake her last days. Instead, Maynard moved to Oregon to have access to that state’s first-in-the-nation right-to-die legislation.

There, she died as she had planned.

Legal aid in dying already has a foothold of national public support. Surveys show most people support this as long as there are adequate legal safeguards such as limiting access to mentally competent adults.

Gallup, in a national poll in May 2015 using the hot-button word “suicide,” found that 68% of U.S. adults said, “When a person has a disease that cannot be cured and is living in severe pain, doctors (should) be allowed by law to assist the patient to commit suicide if the patient requests it.”

Compassion & Choices political director Charmaine Manansala said politicians should pay attention. “Aid in dying doesn’t result in more people dying. It means more people have less suffering.”

Manansala, who is Catholic, cited the statement from Jesuit-seminary-trained California Gov. Jerry Brown, when he signed that state’s law.

Brown said that after deep reflection and wide, diverse consultation he concluded: “I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain. I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by this bill. And I wouldn’t deny that right to others.”

Neither does the law impose participation on people who object. It was elaborately constructed to allow physicians, pharmacies and health care systems to “opt out” on conscience grounds.

The next step, said Matt Whitaker, Compassion & Choices state director for Oregon and California, is to ensure access in a state where the two largest faith-based health care systems, Catholic hospitals and Adventist Care hospitals, have announced they will not participate.

Other large California systems, such as Kaiser Permanente and Sutter Health, are setting up procedures for doctors who say they are willing to aid patients seeking this option.

“People should be able to go to a doctor and have these conversations without facing institutional impediments,” Whitaker said.

Even as California deals with implementing the new law, advocates are stepping up efforts in state after state. Bills modeled on the California law have been submitted in 18 states and the District of Columbia.

New York — where similar legislation passed a health committee in the state assembly in May — could be the next “significant win,” said Manansala.

New Jersey lawmakers will likely hold hearings this summer and Utah has scheduled hearings for July, she said.

In Colorado, a signature campaign is underway to put a referendum, Initiative 145, on the November election ballot.

However, a bill similar to California’s was withdrawn before a committee vote in the Maryland Assembly this spring after a coalition of religious and secular activists lobbied against it.

Opposing forces wield spiritual, social and moral arguments.

Although some religious voices have spoken up for this legislation, across the country, Catholic bishops, Mormons and conservative evangelicals have condemned such bills in one legislature after another. They say humans cannot usurp God’s role as author of life and death.

Secular opponents say the critically ill don’t truly have autonomy. By the time they are eligible for the “option,” they’re in a fog of fear and pain and vulnerable to outside pressures.