Slow-motion goodbye: Rosetta craft makes deliberate dive into comet

After more than a decade of roaming tirelessly across the solar system, the comet-watching Rosetta spacecraft has gone to its eternal reward.

In a deliberate act of self-sacrifice, Rosetta plowed into the surface of comet 67P at 6:39 a.m. ET. Friday. The collision was confirmed roughly 40 minutes later when signals reached Earth from the distant craft, which launched in 2004 and accompanied the comet’s wanderings for the last two years.

At the spacecraft’s operations center in Germany, scientists and engineers were riveted by a green line zigzagging across a dark screen, representing the radio transmission from the craft. In an instant, the up-and-down of the line dwindled and stopped.

Rosetta operations manager Sylvain Lodiot confirmed to his team that the signal had ended and took off his headset. Grim-faced engineers exchanged hugs, some wiping their eyes.

“It’s almost like watching a human being passing away,” NASA’s Bonnie Buratti, NASA’s Rosetta project scientist, said from Germany. “The radio signal flat-lined, and we knew.”

The spacecraft’s death plunge reunited it with sidekick Philae, which landed on the comet in late 2014 and quickly stopped communicating with Earth.

Philae now lies sleeping in a dark crack halfway around the comet from Rosetta’s final resting place. But on Friday the lander’s official Twitter account sent out the plaintive message, “#Rosetta, is that you?”

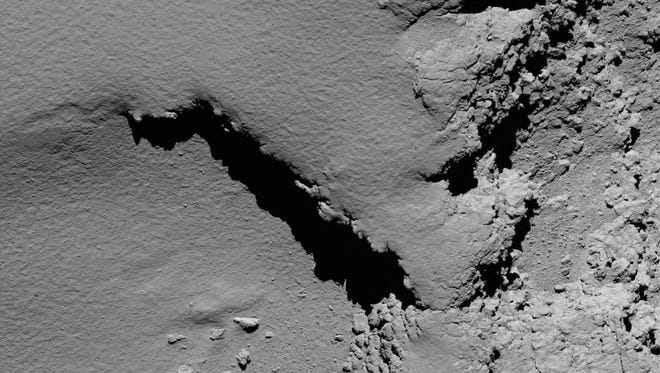

Rosetta, hardworking to the last, sent back photos of the comet taken from 16 feet above the surface, showing gravel fields and craggy boulders.

“The spacecraft and instruments operated exactly as expected right up to the end of the mission,” Christopher Carr of Britain’s Imperial College London, who headed one of the spacecraft’s instrument teams, said via email. “We’re all quite emotional here at the control center.”

Rosetta’s suicide was a slow-motion affair. The spacecraft, operated by the European Space Agency, spent 14 hours free-falling toward the comet’s pitted Ma’at region. It hit the dusty surface at a mere 2 mph – barely walking pace.

But the craft was designed for flying, not landing, so even this slow-motion crash could very well have broken off Rosetta’s long, spindly solar panels or other crucial components.

No one will ever know whether the ship survived intact. At the moment of impact, the vehicle’s systems were shut down, partly to comply with rules about radio transmissions in space. The chances of Rosetta ever breaking its silence again are nil.

Rosetta’s two-year sojourn at comet 67P, more formally known as Churyumov-Gerasimenko for its Ukrainian discoverers, was a glorious era for the study of comets, bodies of rock and ice that are remnants of the early solar system. Never before had a spacecraft accompanied a comet through space, much less traveled alongside it as it heaved and belched while passing close to the sun.

The mission reaped so much data that scientists have barely begun to analyze it. Now that the hard work of operating the spacecraft is over, researchers will begin to dig into the spoils, which will keep them busy for decades

While scientists look forward to delving into the data, they are also wistful about Rosetta’s end. It will be the last sustained mission to a comet for years, perhaps decades, and the next scientific challenge – bringing a sample of a comet back to Earth – is a major technological leap.

“There is no mission in the future that will do anything like Rosetta,” Carr said shortly before the spacecraft’s crash-landing. “It has been groundbreaking… and now it’s coming to an end.”