Families of World War II MIAs sue to identify remains

MILWAUKEE — Families of seven military members killed in the Philippines, including the first American soldier awarded the Medal of Honor in World War II, sued the government Friday to get their loved ones' remains identified and returned home for burial.

A lawsuit filed in federal court in Texas seeks a judge's order to compel the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency to exhume the remains buried in an American military cemetery near Manila, identify them, and allow their families to finally bury them with full military honors under headstones with their names.

The agency handles the search and identification of tens of thousands of American troops considered Missing in Action from all wars.

Wisconsin lawyer Benoit Letendre, a specialist in veterans law, filed the lawsuit on behalf of the families at the request of the Madison-headquartered Pfc. Lawrence Gordon Foundation, a non-profit that looks for MIAs and advocates on behalf of their families.

"We have seven plaintiffs who have been working, some for the better part of 40 years, to convince the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency that these common graves contain the remains of their loved ones," said Letendre, who served 10 years in the Marines including deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan.

Read more:

Korean War hero laid to rest in Louisiana after 66 years

Report faults Pentagon efforts to find MIAs

WWII airmen, segregated by race, finally meet decades later

The seven men were killed in action; one was executed by the Japanese, another survived the Bataan Death March only to die of disease in a POW camp. The families believe their remains are buried in graves marked "unknown" at Fort McKinley Military Cemetery near Manila. Records pertaining to their remains were classified until a few years ago.

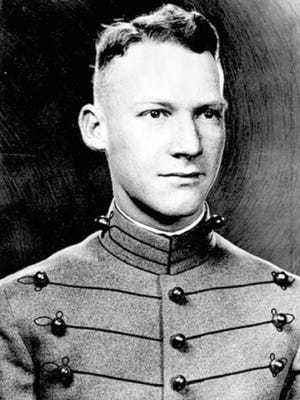

The lead plaintiff is the family of 2nd Lt. Alexander "Sandy" Nininger, a 1941 West Point graduate sent to the Philippines with the 57th Infantry Regiment. On Jan. 12, 1942, Nininger volunteered to join another company under attack by Japanese troops on Bataan.

According to his Medal of Honor citation, Nininger repeatedly forced his way into the enemy's position, attacking with his rifle and hand grenades to kill Japanese snipers and soldiers in several foxholes. Wounded three times, Nininger continued fighting until he was killed. He was 23.

"He was the hero of my life," Nininger's nephew John Patterson said. "I was 6 when he died and I remember the reaction of my mother to the news that he had been killed. She was just hysterical. Really I don't think she was ever the same because they were very close."

Patterson said that after U.S. war graves registration officials couldn't find his body because of the erroneous information from the unit’s commander, Nininger was deemed unrecoverable. But Patterson interviewed members of the unit who told him where Nininger and four other officers killed within 24 hours of each other had been buried.

Nininger's remains were disinterred and identified but the identification was later overturned by officials because of what was perceived as a discrepancy in the length of a femur bone.

"We're convinced because of other things being similar, like dental records, that we know who he is and where he's buried and we want the government to disinter the remains," said Patterson.

Patterson has given samples of his DNA to test what he believes are his uncle's remains, but he said that despite repeated requests, the government has refused.

The plaintiffs also include the family of Brig. Gen. Guy O. Fort, who led his troops against the Japanese on Mindanao until his superiors ordered him to surrender. His soldiers continued to fight, and despite entreaties by Japanese military commanders, Fort refused to persuade them to stop. Fort was executed by a firing squad — the only American-born general officer executed by enemy forces.

Also part of the lawsuit is the family of Arthur "Bud" Kelder whose next of kin, Douglas Kelder, lives in Shell Lake. Kelder died of disease and malnutrition in Cabanatuan POW Camp on Nov. 19, 1942, and was buried with several other prisoners who died that day.

Part of Kelder's remains were identified a few years ago through the efforts of his cousin John Eakin, who successfully filed the same type of lawsuit in the same court — the Western District of Texas in San Antonio — as Friday's petition. Eakin said he was stonewalled when he tried to get information about Kelder and ended up filing a Freedom of Information Act request, which led to the release of thousands of records on MIAs.

Eakin checked the records of the remains of 10 men mentioned in Kelder's personnel file, and when he read of one set of remains with gold teeth fillings — which Kelder had — he told government officials.

"I was under the assumption the government would jump all over this because they said they wanted to get all these guys back. Turned out it wasn't true. They flat out told us they were not going to exhume those remains," said Eakin, a Vietnam veteran who lives near San Antonio.

A judge ruled in favor of Eakin in the lawsuit — Kelder was identified and buried in Chicago in 2015, but later Eakin learned that the government only handed over part of his cousin's remains.

That's why his family is part of the lawsuit filed Friday.

"I think the government would be very foolish to try and defend their action," Eakin said. "I'm sure we'll get the remains, but the real battle is will the government do what they should have done 70 years ago and properly identify these men?"