A sharpened debate: Is it ethical to not vote this year for president?

The most controversial presidential campaign in modern American history has sharpened a long-standing debate: Is it ethical to not vote?

More than 92 million Americans who were eligible to vote four years ago didn't cast ballots. But politics in the Age of Trump has prompted editorial writers, Democratic partisans and even some Republicans to argue that Donald Trump is so unacceptable as a potential commander in chief that citizens have a heightened duty to show up to cast their ballot against him.

Some Trump supporters, presumably including those who chant "Lock her up!" at GOP rallies, feel the same way about Hillary Clinton.

"Let's be clear: Elections aren’t just about who votes, but who doesn’t vote," first lady Michelle Obama said last week at a Clinton campaign rally at La Salle University in Philadelphia, with a cautionary message aimed at Millennials. "And if you vote for someone other than Hillary, or if you don’t vote at all, then you are helping to elect Hillary’s opponent. And the stakes are far too high to take that chance, too high."

Conservative columnist Dorothy Rabinowitz struck a surprisingly similar tone in a message aimed at Republicans.

"Some among the anti-Hillary brigades have decided, in deference to their exquisite sensibilities, to stay at home on Election Day, rather than vote for Mrs. Clinton," she wrote in Friday's The Wall Street Journal. But she warned, "Her election alone is what stands between the American nation and the reign of the most unstable, proudly uninformed, psychologically unfit president ever to enter the White House."

On Team Trump, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie and former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani are among those who argue it is Clinton whose election would pose a threat to the republic. And some Republicans who oppose Trump make the case for sending a message by supporting a third-party candidate or not voting at all.

Former Florida governor Jeb Bush, vanquished by Trump in the GOP primaries, told reporters Thursday after delivering a guest lecture at Harvard University that he planned to vote, but not for Trump or Clinton. "If everybody didn't vote, that would be a pretty powerful political statement, wouldn't it?" he said.

FEAR VS. HOPE

Trump's temperament — criticism of Muslim-American Gold Star parents, a late-night Twitter storm against a former beauty queen — and policy views that include skepticism of the NATO alliance and admiration for Russian President Vladimir Putin have fueled alarm even among some life-long Republicans about whether he should be trusted with the nation's highest office. Former president George H.W. Bush and 2012 presidential nominee Mitt Romney are among those who have said they won't vote for Trump.

But concerns about Clinton, including questions about her honesty and trustworthiness, have complicated the calculations by some voters about just whom to support. All that has boosted Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson, whose 7.3% level of support in the RealClearPolitics average of recent nationwide surveys is higher than any third-party candidate on Election Day since Ross Perot in 1996.

When both major-party candidates get negative ratings from most Americans, will more voters just stay home?

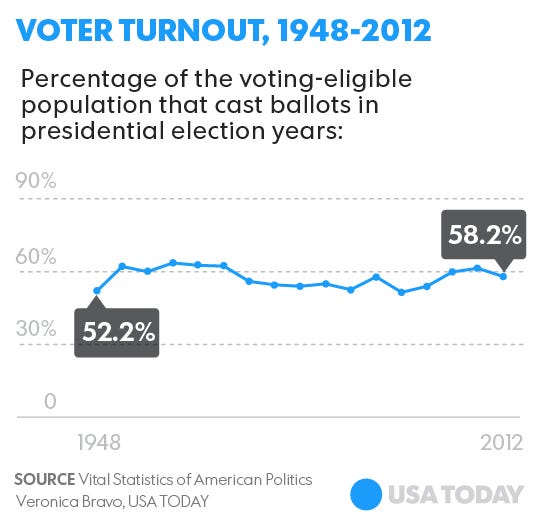

Inspirational contenders tend to do best in drawing voters to the polls. The highest rate of turnout since World War II was 63.8% of the voting-eligible population in 1960, when a youthful Massachusetts senator John F. Kennedy narrowly won the White House. After decades of more-or-less steady decline, it spiked again to 61.6% in 2008, when Illinois senator Barack Obama was elected the nation's first African-American president.

But scholars say fear can be as compelling as hope.

"Fear is a pretty big motivator, just as is enthusiasm," says Michael Dimmock, president of the non-partisan Pew Research Center, which has studied voters and non-voters. Turnout in presidential elections tends to dip in years such as 1996 and 2000, when voters don't see the stakes as particularly high or the differences between the two major candidates as particularly sharp.

Neither factor would apply this time. And high levels of interest this year may signal higher turnout.

In a Pew study released this summer, more than eight in 10 said they were following news about the candidates closely, the highest level of interest in a quarter century. Eight in 10 said they had thought "quite a lot" about the election. Three of four said it "really matters" who wins.

That said, two-thirds called the tone of the campaign too negative, and only four in 10 were satisfied with their choices, the lowest level in two decades. Just one in 10 said either candidate would make a good president. Four in 10 said neither would.

"We've never had candidates like this for president," says Michael McDonald, a political scientist at the University of Florida who heads the United States Elections Project. He turns to Senate races for comparison, citing the 2010 Delaware contest when Democrat Chris Coons crushed Republican Christine O'Donnell. She was a controversial Tea Party-backed contender who, among other things, aired a TV ad denying she was a witch.

Despite a contest that wasn't seen as competitive, turnout in the First State was among the highest in the country last year.

"My guess is people are going to be activated to vote against these candidates," McDonald says. "They may not like their particular candidate ... but they certainly don't like the other party's candidate."

"It's not: 'How much do I like these people?'" says Jan Leighley, an American University professor and co-author of Who Votes Now? Demographics, Issues, Inequality and Turnout in the United States. "It's: 'Does it make a difference between this person I do not like opposed to that person I do not like?'"

This year, Trump has heightened that issue with rhetoric that seems "outside the scope of reasonable conversation or respectable public dialogue," she says. If he continues to do that, she says the question for voters could be this: "Is one being irresponsible by not casting a ballot?"

In the first, tentative clues about turnout this year, McDonald says requests for absentee ballots in congressional districts in Iowa, Maine and North Carolina likely to favor Clinton have been running slightly ahead of requests at this point four years ago. Requests in districts in those three states likely to favor Trump have been running slightly lower.

WHO DOESN'T VOTE?

"Most Americans think there's an obligation to vote," says Jason Brennan, a Georgetown University professor and author of The Ethics of Voting, though the percentages may be inflated because they think that's what they're supposed to say. He doesn't agree, likening it to a lottery, when an individual ticket or vote isn't likely to make a difference.

That said, he generally does vote himself.

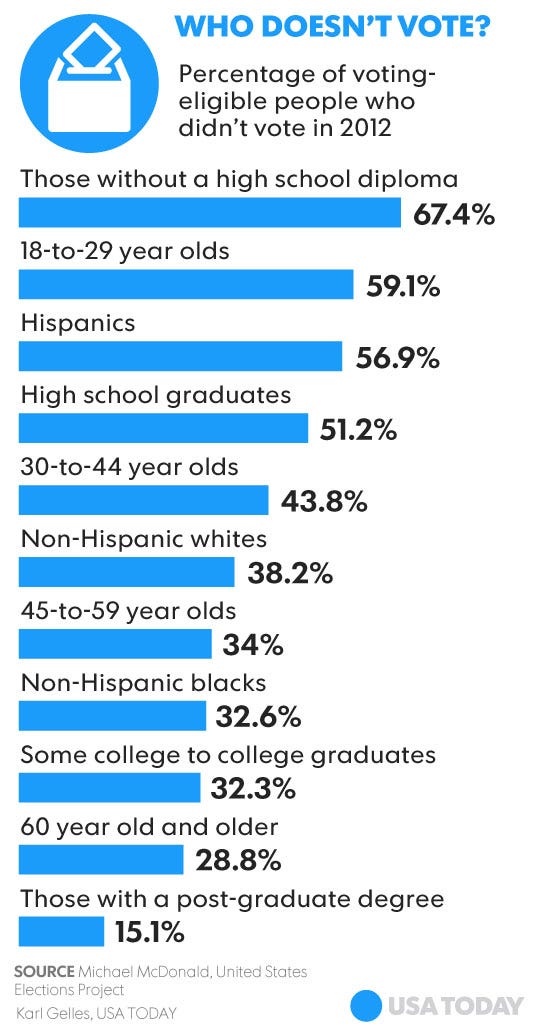

A look at the demographics of those least likely to vote explains why Democrats are more focused on turnout efforts than Republicans. A majority of eligible Latino voters and of voters under 30 didn't go to the polls in 2012. Both groups support Clinton over Trump, and they make up significant blocs in some battleground states — Millennials in Colorado and Virginia, Hispanics in Florida and Nevada.

Clinton has vowed to encourage 3 million new Americans to register to vote before Nov. 8. She and her top campaign surrogates increasingly are focused on registering voters before state deadlines loom and encouraging supporters to cast early ballots.

That said, Trump has done well among another group of voters not inclined to cast ballots: Those who don't have a college education. Only a third of eligible voters who don't have a high school diploma voted in 2012, and less than half of those with only a high school education did so.

Most non-voters stay away from the polls not because they are making an ideological statement but because they say they are too busy, or they don't like either candidate, or they don't think it matters if they vote. As a group, they are younger, less educated and less affluent than voters. They express less interest in politics and public affairs, although a USA TODAY/Suffolk University poll of unlikely voters in 2012 found two-thirds of them said they were registered.

They are much more likely than voters to favor an activist government; eight in 10 said the government plays an important role in their lives. And the USA TODAY survey found they supported Obama over Romney by more than 2-1, a far wider margin than those who cast ballots.

Get-out-the-vote efforts, a standard part of presidential campaigns for decades, have started earlier than ever this year, in part because of the rise in early voting. An estimated four in 10 voters will have cast early or absentee ballots before the polls open on Nov. 8. The GOTV campaigns also have taken on a fiercer intensity than, say, when the choice was between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney.

"I agree with the premise of The Arizona Republic, The Detroit News and many others that Donald Trump is a unique kind of candidate who represents a unique kind of threat to our fundamental way of life," says Norman Ornstein, a veteran political analyst at the American Enterprise Institute. USA TODAY, which in the past hasn't endorsed a presidential candidate, on Friday came out against Trump, urging voters to go to the polls to support someone else.

Ornstein acknowledges some voters are wary of Clinton as well. "Even if you see it as the lesser of two evils," he says, "one of those evils is going to become president."