Europeans who join Islamic State leave parents fretting they'll die

PARIS — Veronique Loute hoped her son was not in a combat zone last year after the war against the Islamic State heated up in Iraq and Syria.

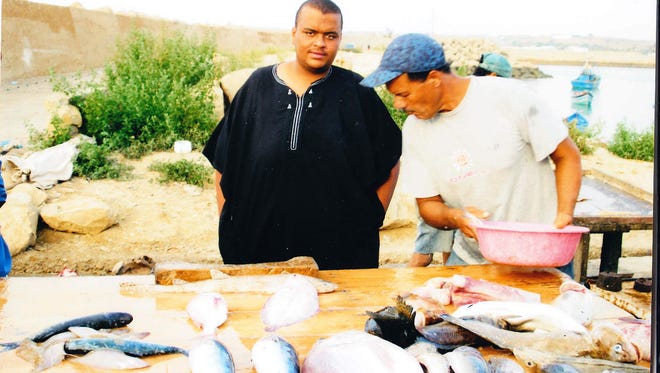

Her son, Sammy Djedou, 27, was among the first Belgians to join the militant group when it grew in power in Syria and Iraq nearly three years ago. She hadn’t seen or heard from him since August 2015.

"He never told me where he was,” she said in an interview. “It's not impossible — since he has a family with two children — that they fled when they found out what was about to happen. I am just hoping he is safe and that he is not taking part in this horrific war."

As U.S.-led coalition warplanes bombard northern Iraq and Syria, many other Belgian and French parents of children who have joined the Islamic State, also known as ISIL or ISIS, are in agony along with Loute. They ask why their children joined a group that commits atrocities and imposes a draconian interpretation of Islam on those living under its rule, and they worry coalition forces will kill their offspring.

"It's a constant tug of war," said Amelie Boukhobza, a psychologist in Nice, France, who specializes in the psychopathology of radical Islamists. "The families would be very happy to see the destruction of the Islamic State because their children would no longer be under its influence. But at the same time, it's their children who are being targeted."

Foreign fighters began leaving home to join the Syrian uprising against President Bashar Assad's regime in the summer of 2012, according to a study released last year by the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, a think tank in The Hague.

Since then, the number of fighters who traveled to battlefields in Syria and Iraq has grown significantly. About 4,000 foreign fighters departed from Europe, with two-thirds originating from Belgium, France, Germany and the United Kingdom.

Some don't return. Belgian security officers called Loute in December with terrible news: A drone attack killed Djedou and two other militants as they drove a car in Raqqa, the Islamic State’s de facto capital in Syria.

Djedou, who went by the name Musab al-Belgiqi, was an Islamic State leader who helped plan the November 2015 terror attacks in Paris and the March attacks in Brussels, the Pentagon said in a December statement that confirmed his death.

Loute, who remembers her son as a loving boy, cannot fathom he would commit such atrocities. "My son really does not have the shoulders or the mindset to do such things,” she said. “It's not him. It's not possible."

Parents like Loute often have a hard time believing their children have become radicalized, said psychiatrist Patrick Amoyel, founder of the Entr'Autres Association in Nice that works to fight extremism.

He said denial is a defense mechanism: Parents choose to believe their children have been duped. Sometimes, they refuse to believe their child is dead. “We've seen this very often," he said.

In 2013, Valerie de Boisrolin's daughter, Lea, 20, left for Syria with a man she met online and later married. The mother was caught off guard. "She wasn't a troubled kid,” de Boisrolin said. “We have been devastated to learn she was in Syria."

For her, Lea is a victim. "In my eyes, my daughter has been abducted," de Boisrolin said. "I don't think she knew what she was getting into, and once she wanted to come back, it was not possible. Maybe it's dangerous for her."

Guilt often consumes parents. Many blame themselves for failing to provide a stable home life that would give their children the fortitude to withstand radicalization, Amoyel said.

Would-be recruits, often descended from Muslim immigrants but growing up in families that lived in Europe for generations, are looking look to reconnect with the Arabic and North African cultures that their great-grandparents and grandparents left behind to search for a better life.

Contemptuous of the European societies where their communities are marginalized in ethnic enclaves, they reclaim an Islamic identity as an act of redemption, he said.

Lea used to be in contact with her mother via WhatsApp or Skype, but she stopped calling since July, and no one knows her whereabouts.

Since Iraqi forces began a siege last fall to recapture Mosul — Iraq's second-largest city — from the Islamic State, the violence has disrupted communications between many fighters and their parents, Amoyel said.

Some youths also cut ties with their parents as their ideological fervor intensifies, and their parents try to convince them to come home, the psychiatrist said. "At some point the children think it's no longer worth arguing."

Parents realize their children could one day launch terror attacks in Europe. "Every time there is an attack, they need to know who carried it out, they need to rule out the possibility it can be their own child," said Nice psychologist Boukhobza.

De Boisrolin consoles herself with the fact that few women are combatants, but she’s still worried.

"I feel responsible every time something happens on French soil. We imagine the worst,” she said. "It's a state of profound sadness. We feel totally disarmed.”